People pay all that money to sit in a chair in the theatre mainly because it is a respectable way to see and experience things they cannot see and experience in their own lives. – Elizabeth Ashley

Note: The idea for this artefact was inspired by the article “5 Questions to Consider When Pricing Smart Products” by Nicolaj Siggelkow and Christian Terwiesch published in Harvard Business Review in July 2019. I thank them for their wonderful ideas.

The Price for a Cup of Tea

My hometown, Thiruvananthapuram, situated in Southern India, has numerous teashops across its streets. Some of them are big and some of them are small. Priced competitively, these teashops sell everything from tea and coffee to freshly made snacks. These teashops are also popular amongst office goers not just for its price, but also because of how easy it is to buy, consume, pay, and walk away – the snacks are already ready, the tea takes hardly a minute to make, and the payment is mostly in the multiples of INR5 or INR10. No wonder some of the more popular teashops in Thiruvananthapuram sell more than 1,000 cups of tea every day.

They are also quite popular for one more reason – they do not increase their prices at the drop of a hat when the prices of milk, sugar, or tea powder go up. In fact, if I remember correctly, the price of a cup of tea, with milk, sugar, and enough tea powder has been INR10 for the last few years. Even though the price of milk has gone up by nearly 60% in the last five years.[1]

But why did they not change their price frequently? And it prompts a larger question – why don’t more established restaurants change their prices frequently?

One of the reasons that teashops don’t change the price of tea, or snacks is the fact that the price of INR10 is easy to handle and calculate. For the shopkeeper as well as for the customer. You see, during peak times, these shops sell more than 5 cups of tea a minute, and it becomes tough to calculate the price of different orders and give back change when the prices are not easy numbers. Imagine the trouble of giving back INR9 to a customer who ordered 3 cups of tea and gave INR30 to the shopkeeper.

While I enjoyed my cup of tea at the same price, my friend told me that some of the teashops had recently increased the price of a cup of tea from INR10 to INR12. For someone who has nearly 3 to 4 cups of tea or coffee a day, this sudden price increase can disrupt personal spending. But I was more intrigued about the odd number – twelve – which was the new price for a cup of tea. It was not easy – to handle or calculate.

My friend also had a possible explanation for this price increase to an odd number. He said that in the last two years, the way people pay at the teashops has changed. From giving coins and notes, people are now using their phones and paying through their digital wallets. For some of the most crowded teashops which happen to be near offices, we can safely assume that more than three out of every four transactions happen through their mobile phones, thus eliminating the need to handle cash.

You see, the way we make the payment decides the price of an item. Moving from a physical process to a digital process helped the seller to charge nearly twenty percent more than he usually would have while ensuring the customer does not have to face the prospect of a reduced cuppa. Or in other words, the answer to the question of how we make a payment is an integral part that decides the price of an item.

There are other questions too that will decide the price of a product or a service. And as you read through the list of questions, it is important to remember that all factors may not play a critical part in the price of the product or service but multiple questions and their answers may be important in deciding the price of an item.

Some Important Questions

I believe that the price of a product or a service is decided by the following questions:

- What is the product that is being paid for?

- When is the payment being made?

- Why is the customer paying?

- Who is paying for the product?

- Who is using the product?

- What is the currency that is used for paying?

- Where is the product bought, and where will it be consumed?

- How is the payment being made?

- What is the quantity related factors of a purchase such as how many, how long etc.?

- What is the context under which the product is bought?

While the answers to most of these questions are straightforward, we need to understand that some of these questions can be tricky to answer and may not elicit a straightforward answer. It is also important to note that all these questions are like a tightly coupled network of nodes. A change that may affect the answer to one question may significantly affect the overall price of a product or a service and may negate or exaggerate the effect of all other questions.

Let us take each of the questions and their impact.

What Is the Product That Is Being Paid For?

Perhaps there are very few quotes in Marketing that are as famous as the one by the legendary Harvard Business School marketing professor who said that “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!” Or in other words, the real job of organizations is to understand what the customer wants to get done.

Everyone has a need, and this need decides what the product is used for, and ultimately the product or the service itself. This translates to the value the product delivers, which dictates the price of the product. Understanding this can help organizations not only design and price the main product but also design and price its alternatives that will drive optimum results – both for the organization and for the customer.

For example. When Netflix or Disney Plus price their subscription packages, they are not selling access to a catalog of movies, but rather selling unlimited access to entertainment for their customers. The competitors of Netflix or Disney are not just the other streaming platforms, but also movie screens and other platforms like Twitch, the video game streaming platform, or TikTok, the short video platform, that offer other forms of entertainment and compete for the users’ attention and time.

Let us stick with Netflix and other streaming providers for the moment. While Netflix offers an all-or-nothing package for its users, there will be a category of users who may not need a similar package. There will be people who will prefer to pay for each movie as and when they watch it. YouTube Movies offers such customers an option to rent or buy movies from their platform for a fee that is different for each movie and is paid for each movie. While these charges may be close to the monthly subscription cost of some of the leading streaming platforms, the customers are not burdened with the cost of paying a subscription fee every month. Again, the need differs. And hence the pricing. But the customers get faster access to movies before they hit other streaming platforms.

Now, let us look at YouTube Movies. For most of the movies the customer gets two options – access to standard definition content, or access to a costlier high-definition content. For a customer who has access to a high-definition television and wishes to access high-definition content, the costlier option makes sense.

And for anyone who wishes to access a movie without paying anything, the shady channels of Telegram, and risky torrent websites are always there. But they are not free. The chances of being taken for a ride in these options are high – customers either pay with their data or pay with the risk of downloading a virus along with the movie.

You see, the same movie, or in other words, the same product can be available across the channels. Yet, the pricing differs based on the needs of the customer. If you need it faster, and on demand, you pay more. If you are OK with waiting for a few months, you pay a bit less. And if you are trying to save money for your next trip, and want it for free, then take a risk and go to Telegram or click one of the shady-looking links on YouTube that says, “Free full movie for download.”

In short, the product, and the true need to which the product caters, is one of the fundamental questions that need to be answered to decide the price of a product.

When is the Payment Made?

Would you rather pay for your newspaper subscription every day, or would you rather pay at the beginning of a month, or at the end of a month? All three modes exist in the world of the publishing industry and each of them has a different impact on pricing.

The New York Times costs nearly $4 for the home delivery of its editions from Monday to Saturday and the Sunday edition is a bit more costly. The digital edition costs $1.50 per week, and if you take an annual subscription (or in other words, you pay early), the costs are far less. Let us also not forget the frequent promotions that New York Times runs to attract more subscribers. Ultimately, the price of a New York Times subscription is decided by the time that you decide to make the payment.

The time of the payment differs in many ways and drives the price in more ways than you can imagine.

For example, we live in a world where the price of the insurance policy for your car may differ based on the number of miles that you drive.[2] You drive more, and you pay more. And it makes sense. If you drive more, the chances of an accident are higher, and it is logical that you pay more for insurance. Rolls Royce charges airlines not for the engines that they deliver, but by the number of hours that the airlines use their engine for.

In fact, the subscription economy has changed the concept of ‘when’ we pay. From a world where the price was paid upfront, we live in a world where we pay every month, or when we use something. This shift is evident across the world. Companies like Microsoft which were traditionally reliant on license revenue have moved onto a subscription-based model and earning big bucks.

Why Is the Customer Paying?

Customers buy a product or avail themselves of a service because they need to address a fundamental need. And the true fundamental needs that are addressed decide the price of a product.

Let me explain with an example.

A fast-food restaurant chain wanted to improve its revenue by pricing its products better and they hired a consultant to do the same. Based on research, they found out that the milkshake was one of the biggest contributors to their overall revenue, and the restaurant chain wanted to improve the pricing of its milkshake to get better revenue. As HBR points out, “the researcher spent time seeking to understand the jobs that customers were trying to get done when they hired a milk shake. He chronicled when each milk shake was bought, what other products the customers purchased, whether these consumers were alone or with a group, whether they consumed the shake on the premises or drove off with it, and so on. He was surprised to find that 40 percent of all milk shakes were purchased in the early morning. Most often, these early-morning customers were alone; they did not buy anything else; and they consumed the shakes in their cars. The researcher then returned to interview the morning customers as they left the restaurant, shake in hand, in an effort to understand what caused them to hire a milk shake. Most bought it to do a similar job: They faced a long, boring commute and needed something to make the drive more interesting. They weren’t yet hungry but knew that they would be by 10 a.m.; they wanted to consume something now that would stave off hunger until noon. And they faced constraints: They were in a hurry, they were wearing work clothes, and they had (at most) one free hand. Sometimes, he learned, they bought a bagel. But bagels were too dry. Bagels with cream cheese or jam resulted in sticky fingers and gooey steering wheels. Sometimes these commuters bought a banana, but it didn’t last long enough to solve the boring-commute problem. Doughnuts didn’t carry people past the 10 a.m. hunger attack. The milk shake, it turned out, did the job better than any of these competitors. It took people twenty minutes to suck the viscous milk shake through the thin straw, addressing the boring-commute problem. They could consume it cleanly with one hand. By 10:00, they felt less hungry than when they tried the alternatives. It didn’t matter much that it wasn’t a healthy food, because becoming healthy wasn’t essential to the job they were hiring the milk shake to do. Once they understood the jobs the customers were trying to do, however, it became very clear which improvements to the milkshake would get those jobs done even better and which were irrelevant. How could they tackle the boring-commute job? Make the milk shake even thicker, so it would last longer. And swirl in tiny chunks of fruit, adding a dimension of unpredictability and anticipation to the monotonous morning routine. Just as important, the restaurant chain could deliver the product more effectively by moving the dispensing machine in front of the counter and selling customers a prepaid swipe card so they could dash in, “gas up,” and go without getting stuck in the drive-through lane. By understanding the job and improving the product’s social, functional, and emotional dimensions so that it did the job better, the company’s milk shakes would gain share against the real competition—not just competing chains’ milk shakes but bananas, boredom, and bagels.”[3]

Ultimately, by understanding the real reason why customers bought their milkshakes, they could price them better, and provide greater value to their customers.

Customers do not buy a product, they buy something, and it can be anything, that gives them value and gives them a solution to the problem they are facing. And this is the answer to the ‘why’ of every purchase. And organizations that understand this will succeed in the game of pricing.

Who Is Paying for The Product?

Do you know what a “pink tax” is? I am not sure who coined this unique phrase, but the term gained popularity in the mid-1990s and 2000s. It refers to the phenomenon in which products marketed to women are priced higher than similar products marketed to men. For example, women’s razors, usually packaged in pink or feminine-colored packing are priced higher than men’s razors even though both may have similar features or functionalities. It is a clear, though an unfortunate example, of a price that differs on who is paying for the product, or who the intended audience of the product is.

Another example can be found from the old times, but thankfully, it is not a case of gender discrimination. The marketplaces of the old times were unique places. It can be considered the birthplace of personalized pricing. And probably the first place to have used the concept of dynamic pricing to its fullest extent. With only a few shoppers and even a smaller number of shops, the shopkeepers instinctively knew about the willingness to pay and the capability of individuals to pay. Through a set of indicators, these shopkeepers, most of whom were experts on body language, could identify the maximum price that an individual would be willing to pay for a product or service. Guess the MRP tag has saved a lot of us.

The answer to the question ‘who is paying for the product?’ has been the basis for two of the fundamental and most practiced innovations in the world of pricing – dynamic pricing, and personalized pricing. This phenomenon, also commonly referred to, and sometimes wrongly referred to as price discrimination, has been driving the way organization price their products for the last several decades.

Every innovation that you see around these days, including surge pricing, or hyper-personalized pricing are off shoots of organizations trying to find an answer to this question. And I believe this phenomenon will continue in the future also, and will probably become stronger as organizations rely on, and leverage humongous amounts of data.

Who Is Using the Product?

The Utama One Mall on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur is huge. Because of its distance from the main city, and because of its new stature, crowds are limited in the mall. But the mall houses some of the biggest brands and has one of the best-reviewed play areas for kids in Kuala Lumpur.

They use an innovative pricing mechanism. They charged anywhere between RM30 to RM40 for a single entry, and if adults need to accompany them, the adults are charged a very low fee of RM8. They know that there is very little adults can do than wait for their kids to play, hence the low price.

Let us consider the reversal of roles. Have you been to a theme park? Chances are the kids will be charged very little, and the lucky ones may be let in for free compared to the adults. Because the number of rides a toddler or a small kid can get on will be limited. That makes sense, right?

It is also an open secret that adults may not hesitate to spend a lot more when they buy a product for their significant other, for their kids, or for their parents.

A lot of the above situations come because of reasons such as the emotional value that a product has, the social norms, the need to celebrate occasions, and concepts such as reciprocity, altruism, and generosity – a lot of which are inbred into humans.

Ultimately, the price of a product is not just dependent on who buys the product but also will be decided by the person who uses the product. And organizations that can find out the real answer will reap unmatched benefits.

What Is the Currency That Is Used for Paying?

Do you know the real reason why a lot of gamers end up spending a fortune on their favorite game, often buying frivolous things such as a unique costume, or a fancy leash for their virtual pet? And do you know the reason why some of these virtual games that have a marketplace built within their gaming ecosystem are so successful, and sometimes have valuations that run into several billion dollars?

The answer to both questions is kind of the same – most of these games do not sell products for money, but they sell them in return for tokens, or a form of virtual currency that is different for each game. Apparently, such virtual tokens create a sense of psychological detachment and promote less careful spending. It can also trigger impulse spending. And thus increase the overall revenue of the organization. And because games want their users to spend more, the price of each of these tokens is ridiculously low.

It is also the reason why people do not mind when they end up spending a lot of time on ‘free’ sites such as Facebook and Instagram. Little do they realize that the currency they are paying with is their data, and it may be worth a lot more than they think. When you sign up for a ‘free’ newsletter, remember that it is not free, but a privilege that you are getting in return for agreeing to share your email id and other details.

You see, it is important for organizations to identify the currency with which they will take payments from their customer – it can be data in many forms, tokens, or other forms of currency. And this will define the true price that the customers will pay for their product or service.

Where Is the Product Bought, and Where Will It Be Consumed?

Why does a bottle of water cost you more when you buy it in your room at a fancy 5-star hotel than when you buy it from a 7-11 or any other convenience store? Why does petrol cost less in Delhi, the capital of India, than in Mumbai even though Mumbai is closer to the petroleum refineries. Why does the latest model of iPhone cost more in India and less in the UAE?

Indians love gold. India, in fact, has the highest per capita consumption of gold.[4] And a significant amount of gold is brought in by the migrants living in the middle east region. Over the last few years, India, in a bid to make the process simpler, more transparent, and favor more import from UAE decided to levy a lesser import duty compared to other nations for gold that is imported from the UAE. Yet, after the reduction in the import duty, Indians apparently imported only two tons of gold from the UAE in the last seven months of 2022 – a significantly and suspiciously low number.[5]

One of the most important reasons was obvious – most of the gold that was being imported from UAE and other Middle East channels was through informal channels, and the cost difference offset the benefits that would have been provided by the reduction in import duty. While this low number may point to other significant problems, it also points to one key fundamental aspect that drives the global economy forward – the price of an item changes across markets, regions, and nations.

A lot of factors come into play when the final price of an item is decided. Taxes, surcharges, tariffs, import and export duties, transportation costs, and exchange costs are just some of these factors. Most of these factors are different across regions and may even be different across different parts of the same country. And hence it leads to a price differential based on where the product is bought.

But wait, will the price of a product change have based on where it is consumed?

Have you heard about the term corkage fees? It is quite famous in the high-end hospitality industry where you end up paying a fee to the restaurants for brining and consuming your own alcoholic or non-alcoholic drinks. It is kind of like a fee that the restaurant collects for foregoing its revenue from selling beverages. But it is a great example of how prices can vary based on where you consume a product or a service from. The hotel industry charging a bit more for takeaway food is also a good example.

Ultimately, the answers to the question – where you bought it from, and where are you going consume it from – will be two of the most deciding factors that will decide the price of an item?

How Is the Payment Being Made?

I usually pay my electricity bill online. It is easier and more convenient. And I don’t have to stand in a queue. But there is a catch. If I use my credit card, I am asked to pay an additional fee of 0.85% and an additional fee as a tax. I guess it is the fee the electricity company must pay to the payment gateway providers. And if I use Internet banking, I do not have to pay any additional charge. And if I use a digital wallet that is connected to India’s United Payment Interface, then I normally receive a discount.

This kind of price differentiation based on the way we make a payment is quite common across multiple industries. Many SaaS companies give you a discount if you take an annual subscription instead of a monthly subscription. E-Commerce companies provide you discounts if you make the purchase with some of their co-branded cards. B2B sellers provide you with a discount if you are ready to commit a large amount upfront and not in monthly installments. As the popularity and price of Bitcoins grew, there were even retailers who were offering a large discount on any purchase made via Bitcoins or any other cryptocurrencies.

The way we pay is a critical factor in deciding the final price of an item. And it is the responsibility of the organizations to make sure that the customers are offered options, and that the price differential between the most preferred option and least preferred option is not too much.

What Is the Quantity Related Factors of a Purchase – How Many and How Long?

“Buy 1 and get 1 free, Buy 2 and get 3 free, Buy 3 and get 5 free” – A typical weekday offer that may be the catchphrase for your regular Every Day Low Price or Deep Discount store.

Or look at the prices across your local Staples or Office Depot store. The prices per unit of products such as paper or ink cartridges go down drastically as the volumes go up. Wholesalers like Costco, Sam’s Club, and BJ’s Wholesale Club are known for offering volume discounts to their members. Because organizations love customers who buy more.

Organizations also love people who sign-up for a long time. As I said before, monthly subscriptions are always costlier than annual subscriptions. Even concepts like tiered volume discounts or progressive discounts are outcomes of this thought process.

A long-term or large enough commitment deserves reward – that is the accepted behavior that drives this drop in price, even if it comes across as an anomaly to the general concept of hyper-personalization and value-driven pricing. And this thought process will decide the price of a product or a service.

What Is the Context Under Which the Product Is Bought?

Forget everything else that was mentioned in the previous pages. Everything else changes when the context changes.

Let me explain with an example.

It was a normal Monday in Sydney on the 15th of December 2014. Monday blues, and a lot of anticipation for the upcoming Christmas. And as people were busy with their lives, a gunman decided to put a spanner in their plans as he held people hostage inside a central Sydney café. As NBC reported, “Sydney’s public transport system was under pressure because of the siege as several businesses in the city, including major banks, evacuated offices and sent employees home.”[6]

It was at this moment that the prices in Uber shot up by nearly 4 to 5 times. Rides were suddenly outrageously expensive. And people complained. The outrage was quick. And then Uber decided to make all the rides free.

But this price rise and the subsequent price drop were because of how the context changed over the day. No other question mattered – the who, when, and where did not matter as much as the context.

And the answer to this is the most important one that defines the price of any product or service. This is the question that also needs to grapple with the concepts of morals, ethics, and the right and wrong of pricing. Whether it is for a rare drug, or whether it is for the price of a snow shovel after a heavy snowfall, the answer and the price that is the outcome of this answer will not satisfy everyone.

The context can come from several factors – the time of the day, the place, the event that preceded the event, the background of the buyer, and a lot more. The best that organizations can do is to understand the true context of any transaction as much as possible and take a judicious approach, even if it may not always be economically viable.

But the answer to this question will always be a tough nut to crack.

The Final Word

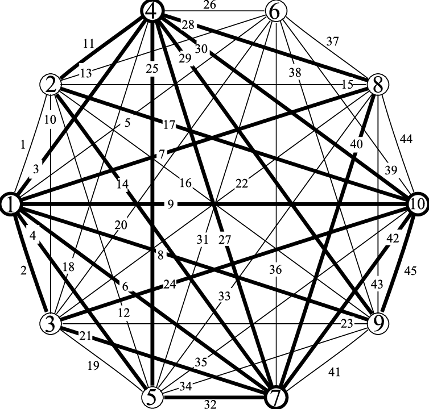

Image taken from Research gate

Each of these questions can be considered as the corners of a decagon like the one shown above – each connected with the other, yet independent by itself. The interactions and impact will be complicated, and the way these questions contribute to the final price of a product may not be in the way an organization may foresee. A small change in the answer to one question may create a drastic impact on the way people perceive a product and may change the answers to the other questions also. Each of these questions is important by itself, yet they do not hold significant value if they are not seen along with the other questions.

These questions determine not just the way products are priced but will also determine the overall revenue that these products will generate, the life of the product, and more importantly the value of the product in the eyes of the customer. And hence these questions become more important.

And organizations that can answer the above questions as much as possible will be the ones that will crack the code of pricing.