An economist’s definition of hatred is the willingness to pay a price to inflict harm on the others. – Edward Glaeser

How Princeton Review Goofed Up Their Pricing Strategy

The United States is a great academic destination. Every year, several thousand high school students in the U.S. and across the world get ready for the SAT by using The Princeton Review’s test preparation services. And curiously, the percentage of successful Asian students who use The Princeton Review, is higher than that for any other ethnicity. While this could be because of their upbringing and cultural focus on education, the correlation with The Princeton Review cannot be ignored.

In the mid-2010s, a Harvard research student realized that the prices of The Princeton Review’s online SAT tutoring packages in the U.S. varied substantially depending on the customer’s ZIP code. Shockingly the prices were higher in ZIP codes with large Asian populations, where the median household income was lower than the national average. In fact, customers in areas with a high density of Asian residents were 1.8 times as likely to be offered higher prices, regardless of income. The uproar was quick and intense. Many customers complained, and politicians and news agencies saw this as an opportunity to connect with the Asian population. The Princeton Review was forced to issue a statement which said that ‘the prices are based on costs of running our business and the competitive attributes of the given market’.[1] In other words, they were saying – we just charged what the customers were willing to pay. This is unethical, but not illegal. And so, the story died its natural death in a few months.

The Willingness to Pay or WTP

Why did The Princeton Review decide to price ZIP codes with significant Asian population more than the other zip codes? While the simple answer is personalized pricing, there is a deeper reason for the same. The neighborhoods that were charged more had couple of things in common – they were mostly Asian, and they were relatively poor compared to the national average and saw the SATs as the ticket to a better future. The perceived value for the package was higher with the Asian population, leading to a higher willingness to pay despite their lower income. Stronger the reason to buy a product or avail a service, the higher the willingness to pay. For example, imagine a scenario where you are travelling back home to attend to a personal emergency. In such a scenario, your willingness to pay for an airline is far greater than if you were travelling for leisure.

How Is It Different from The Ability to Pay Or ATP?

But in many instances, the willingness to pay is high, but the lack of ability to pay will prevent a transaction from taking place. We can call this as the willingness-ability gap. When this gap is positive, or when the ability to pay is greater or equal to the willingness to pay, the customer may buy the product immediately. But when the situations reverse, the purchase is not so straight forward. Remember the case of emergency travel. In many cases, the willingness to pay for the fastest mode of travel will be there, but the individual who may find themselves in that situation may not have the means to pay what they are willing to. A negative willingness-ability gap may lead to new business models. The ‘Buy Now Pay Later’ model is one such business model where organizations are trying to reduce the gap between the willingness to pay and ability to pay.

But What About the Price?

An economist will define price as the amount of money, or any currency, that is expected and paid for any product or service. In an ideal world, the price should be less than both the willingness to pay, and the ability to pay. If it is more than the willingness to pay, but less than the ability to pay, the chances of the product being sold will be less, and if the price is more than both the willingness to pay, and the ability to pay, then the chances of the product being sold are negligible.

Where Does Value Sit in This Relationship?

Value is a measure of the benefit provided by a product or a service vis-à-vis its price and is generally tough to measure though extremely important. Value can be described as a contextual, relative, intangible, and subjective perception of the gain from a product by the customer. Or in other words, value is CRISP. The perceived value of The Princeton Review was higher amongst the Asian population.

Price, on the other hand, is always the monetary amount associated with a product. Value is not the same as price. Price is one of the factors that determine value, along with many other aspects. Value is complex and confusing, whereas price is simple and straight forward. And most importantly, value is more important to a customer than the price. Customers do not buy a product because of the price but buy if for the value it delivers. In an ideal world, the value needs to be more than the price and the willingness to pay and can be more or less than the ability to pay. Organizations which try to alter the balance may end up with a product that may not receive acceptance in the market and will become an excellent case study of flawed pricing.

So, What Determines These Four Factors?

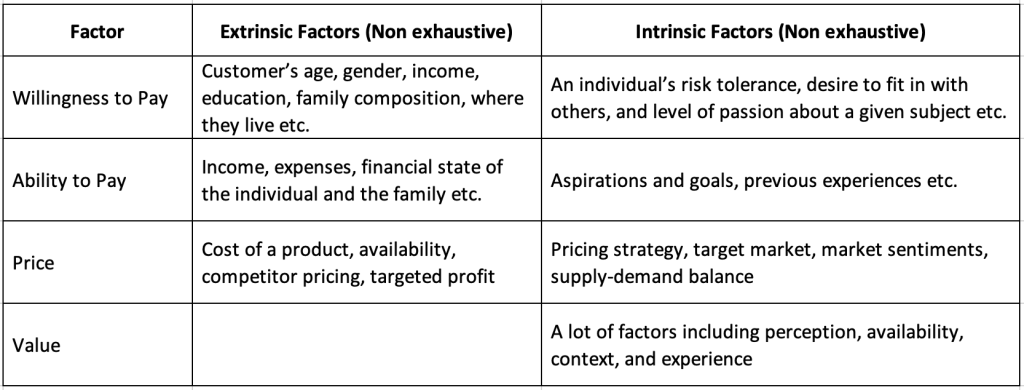

These four elements of a purchase decision depend on a number of factors that can be categorized as extrinsic and intrinsic.[2] Extrinsic factors are usually evident and don’t need any explanations while intrinsic factors are not so obvious.

Apart from value, which is mostly intrinsic, everything else has a relationship with extrinsic factors. It is difficult to understand the exact reason why these factors turn out to be the way they are, and it is nearly impossible to create a completely accurate numerical data-oriented approach to predict these factors. In most cases, it is a combination of all these factors that determine the outcome, and in almost all cases, the intrinsic factors play a stronger role than the extrinsic factors. Accepting these variabilities is a great way to understand the relationship between these factors.

How Can Organizations Find the Right Mix of Ingredients?

Each of these four factors, though dependent on each other, are also independent, and can occur in any order. A wrong mix and order can cause even the best product in the world to fail.

Let us go back to elementary school math. A simple calculation will tell us that there are 24 different possibilities to arrange willingness to pay (W), ability to pay (A), price (P), and value (V). And each of these 24 possibilities are correct within the right context. And can go horribly wrong when the context differs. Let us take a case-by-case approach.

Scenario 1: P<V<W<A

This is the most fundamental scenario. The price of the product is less than the value of the product, which in turn is less than the willingness to pay, which is less than the ability to pay. This is the most comfortable scenario for any organization.

A good example of this scenario would be a discounted common low-price item that a customer values more because of the discount. But they may not be willing to pay beyond a certain point because of its common nature, and because of its easy availability.

The product has a price that is lower than the perceived value –the customer perceives the product to be good deal which may lead to purchase and greater customer satisfaction. Sales discounts, and happy hour sales are great examples of this. The fact that the willingness to pay is less than the ability to pay also indicates that the customer has the sufficient financial resources to pay for the product. And because the WTP is greater than perceived value, the customer may not feel restricted in buying the product. For organizations that are trying to maximize profits, and optimize customer satisfaction, this is an opportunity to reduce the gap between price and value.

Scenario 2: P<V<A<W

Here the ability to pay is less than the willingness to pay – creating a gap between the customer’s financial resources and their willingness to purchase the product.

These scenarios commonly occur for items with medium to high cost that are on a discount. Consider a vacation package that is on discount. Customers perceive the value of the package to be higher because of the quality of the accommodation, activities included, and the overall experience. Yet, because of the high cost of the vacation package, customers may not have the willingness to pay since it may beyond the means of the normal customer.

While the price is lower than the perceived value, the fact that the ability to pay is less than the willingness to pay may result in customers hesitating to buy. Organizations can offset this disadvantage by offering complementary products that reduce the gap between the ability and willingness to pay. In the case of the vacation packages, it can be in the form of zero-interest loans or “buy-now-pay-later” schemes that may prompt the customer to purchase it. Organizations can even offer to reduce the value and hence reduce the gap between willingness and ability to pay by removing certain activities from the package. But because the price is low, these options may not be necessary. They also need to find ways to reduce the gap between price and value and move the price closer to the value – else they are leaving money on the table.

Scenario 3: P<W<V<A

Imagine a luxury fashion product that is conducting a sample sale at a heavily discounted price. Due to the heavy discounts, these products will attract a huge attention of customers who know the true value of the product. And because of the strong brand value, and the ‘luxury’ tag, the value of the product may be more than the willingness to pay of the customer. And all of these may be lower than the ability of a customer who may be a middle-class customer and can afford these ‘lower’ prices.

While discounted offers, exclusive products, and limited availability may shape such scenarios, it is important to note that the organization still can make improvements by reducing the gap between price and value – either by increasing the price, or by reducing the value of the product by offering smaller products, or products with lesser capabilities.

Scenario 4: P<W<A<V

Here because the price is lower than the other three factors, the customer perceives the product as a good deal. And because the willingness to pay is less than the ability to pay, they do not have any financial constraints. And most importantly, since the value is greater than the other three factors, the perceived value is more than the what the customer is willing to pay – thus creating a situation where the price related hurdles are not present.

These kinds of scenarios occur when the customer finds a great deal for an item that is not too cheap or not too costly. In such a scenario, the price is lower than the product which can’t be either a commodity nor is it a luxury item (because the price is not too high, nor too low). And because the product is a mid-range product, their willingness to acquire the product or undergo the experience may not be very high, as he or she may want to keep their expenses under check. And because they are getting a great deal, the value of the product or the service automatically goes up. Mid-range restaurants and affordable vacation rentals that have a decent discount are great examples of this scenario.

Even in this scenario, organizations can move up the price spectrum and gain increased profits. But it is important to understand that increasing the price of the product beyond the willingness to pay may adversely affect the sales of the product.

Scenario 5: P<A<V<W

These scenarios occur when the products and services tend to shift to the other end of luxury or exclusivity, and the willingness to pay will be far greater than the ability to pay for most people.

Let us consider the example of The Deccan Odyssey, a luxury train service in India. The presidential suite in The Deccan Odyssey for a 7-night journey will set a person back by close to $20,000 –more than the total cost of a trip to some Asian countries. But travel enthusiasts are willing to invest a lot in these journeys because of its uniqueness and the experience it offers, even though the ability to pay may be far less. In such a scenario, the price may be far less than the willingness to pay, and the gap between the ability to pay and willingness to pay is the only constraint that may hinder the purchase of a ticket for such a train journey.

It is a great situation for organizations to be in. It also offers a great opportunity for them to increase their prices and gain more profit, especially considering the higher ability and willingness to pay.

Scenario 6: P<A<W<V

In this scenario, since the price is less than the ability to pay, the chances of a customer not purchasing the product or availing the services are quite low. The fact that the willingness to pay is lower than the ability to pay may cloud the customers thought process, but a very high perceived value, coupled with a very low price may push the customer to buy the product.

A great example of this scenario would be the Black Friday sales of a high value item that is heavily discounted. While the willingness to pay – or the mental price the customer would have decided as the maximum price beyond which he or she may not buy the product – is more than the ability to pay, the fact that the product is heavily discounted may make the customer forget this difference.

Organizations can gain more profits and still maintain customer satisfaction by increasing the price to such an extent that it is not beyond the ability of the customer to pay.

Scenario 7: A<P<W<V

The price is greater than the ability of the customer to pay, leading to situations in which the customers do not have the financial means to buy the product. Having said that, the willingness to pay is much more than the price of the product, indicating the readiness of the customer to look for alternative ways to buy the product. The fact that the value of the product is also greater than all three of these factors is also a shot in the arm for the organization, as the customer may not reject the product in an outright manner.

A management degree from an ivy-league college may be a great example for the above scenario. We all know the exorbitant costs for obtaining a degree in management from an ivy-league school, and we all know these costs may well be beyond the means of most customers. Yet most customers have a great perceived value for such a degree because of the potential of the candidate to earn substantially in the future.

In such a scenario, the organization has many options. One can be offering the product price in a regular time-bound manner at pre-defined intervals. Another option is to help the customer reduce the gap between the ability to pay and the willingness to pay by offering student loans with reduced interest rates.

Scenario 8: A<P<V<W

This scenario occurs when customers usually have an affinity for a particular product or have an emotional attachment. For example, a customer may want to buy back a family heirloom that their family lost several years ago, and he or she may be willing to pay much more than the product is worth just because of the emotional attachment and personal significance. In these cases, the value is significantly lower than the customer’s willingness to pay.

As with the previous scenario, because the customer’s ability to pay is less, they may face constraints in completing the purchase and it will be upon the organization to reduce the gap between the ability and willingness to pay.

If it is a family heirloom that is on auction, and the original owner is also looking out to purchase, the auction house, to drive the purchase, can offer on the spot loans or reduce the gap between the ability to pay, price, and willingness to pay by offering financial incentives or discounts.

Scenario 9: A<W<P<V

There are two problems that organizations will face in this scenario – because the ability to pay is less than the willingness to pay, the customer will have financial constraints. And because the willingness to pay is less than the price, the customer is not ready to pay the price for the product as he or she may believe that the price is high.

While organizations will certainly have to offer financial incentives, and discounts to reduce the gap between the ability and willingness to pay, they will also have to reduce the gap between willingness to pay and price.

While the simplest solution would be to bring down the price through discounts, offers, promotions, or through product bundling, it may not be beneficial in the long run. Alternatively, organizations can look at communicating the value their product offers or offering more features or through value-added services and benefits to increase the willingness to pay and bring it closer to the price. Or they can take a segmented approach to offer different versions of product, so that the gap between the willingness to pay and price is reduced in each segment.

Scenario 10: A<W<V<P

Here the perceived value from the product is lesser than the price of the product. This means that the customer may look for low-priced alternatives.

If this situation continues, the chances of the product or the service being sold will be low. To counter this, organizations can adopt different approaches. The most obvious one is to reduce price through discounts, offers, bundling etc. They can also look at targeted communication and include value-added services and benefits to increase the perceived value of the product.

Scenario 11: A<V<P<W

The customer may find the price within their acceptable limits of willingness to pay. But they may not find the product or service to deliver the necessary value in the long run to command such a high price. This may make them hesitant to purchase the product as the price may not align with the perceived value of the product. And because the ability to pay is low, the chances of purchases are very low.

For organizations facing this scenario, it may be beneficial to revisit their pricing strategy and look at ways to enhance the perceived value of the product through an increase in quality, reducing availability, increasing exclusivity, or by adding more value-added features. Organizations may also look at the prospect of reducing prices if that is the only way.

Scenario 12: A<V<W<P

The price is far greater than the customer’s willingness to pay, which itself is greater than the perceived value of the product. This will mean that the offerings are perceived as low value and highly priced – not a good pricing strategy.

While these scenarios may work out in monopolies and situations where the demand far exceeds the supply due to natural or artificial constraints (such as the increase in demand and subsequent hike of price for toilet paper as people stocked up on personal hygiene products as the COVID-19 pandemic started to take shape), these scenarios may not last long. There may be two outcomes – either the businesses that promote these will go out of favor as customers find alternatives, or competition will create lower price points and attract customers.

Organizations must reduce the gap between the ability to pay and willingness to pay, and subsequently reduce the gap between willingness to pay and price.

Scenario 13: V<A<P<W

In this scenario, two things work against the organization.

- The perceived value of the product or the service by the customer is very low.

- The ability to pay is less than the price of the product.

But one thing works for the organization – a high willingness to pay.

This scenario is possible when the emotional attachment of the customer to the product is very high. In such a scenario, the customer may not even have the ability to pay a huge amount for the product, but the emotional attachment towards the product may prompt them to pay a huge price to acquire the product.

But if an organization finds itself in this scenario, it has three options – focus on increasing the perceived value, reduce the price of the product, or focus on both the strategies. Organizations can adopt a mix of different strategies including communicating the value of the product, educating customers, product bundling, and offering discounts and offers to reduce the price of the product.

Scenario 14: V<A<W<P

During the 1630s, tulips were introduced to the Netherlands and became highly sought-after as a status symbol due to their unique colors and intricate patterns. The demand for tulip bulbs grew rapidly, and prices began to rise. The speculative frenzy around tulip bulbs reached a point where people were trading tulip bulbs in futures contracts, with buyers purchasing bulbs at higher prices with the hope of selling them at even higher prices in the future.

You see, the value of the tulips was negligible, but the prices outstripped the willingness to pay as customers were driven by the fear of missing out. And when the market collapsed, many customers lost their money.

Organizations that face these situations will need to quickly revisit their pricing strategies and make sure the perceived value of the product goes up, and the price of the product comes below the willingness to pay.

Scenario 15: V<P<W<A

While the perceived value of the product is still low in this scenario, the willingness to pay is more than the price. The ability to pay is more than the willingness to pay. And both factors will aid in supporting the decision of the customer to purchase the product.

This may not be a common occurrence for day-to-day products where competition is high, and the number of alternatives is more. But this scenario is possible in situations where the product is limited in supply or is exclusive and the customer has a personal attachment to the product. For example, the functional value of a Hot Wheels model may be low. But a collector of Hot Wheels, may be willing to pay a high price for a limited-edition toy, because it may complete his or her collection.

Organizations that have products that fall under this scenario need to choose their strategy as per the needs of the market. In the above scenario, the organization may need to communicate the exclusivity of the model to the customer. But in other cases, the organizations may need to focus on increasing the value of the product through value-added services or through strategies such as product bundling.

Scenario 16: V<P<A<W

This scenario is pretty much like the previous scenario, except the fact that the ability to pay is lower than the willingness to pay. For example, in this case, the customer may still be a collector of toys, but may not be as well off as the customer in the previous scenario.

But organizations need not worry as the price is below the ability of the customer to pay. They need to ensure that the price stays below the ability of the customer to pay and communicate the value of the product on a regular basis with the customer.

Scenario 17: V<W<A<P

While the perceived value is still low in this scenario, the price is on the higher side. It is more than the ability to pay and the willingness to pay. In this case, the customer may either forego the purchase or look for alternatives.

This may become a zone of no-purchase for customers, and it is important for organizations to act immediately – either to increase the perceived value of the product or take steps to reduce the price of the product. Consistent communication, customer education, market research, discounts, and product bundling may be methods through which organizations can address this.

Scenario 18: V<W<P<A

While the perceived value is still low like the last scenario, the key difference is the fact that the ability to pay is more than the price of the customer. The customer may find the product to be expensive but have the means to buy the product even though it may not offer the necessary value in the long run. This is applicable in cases where people buy a product to fit into a crowd and may not really need the product and its full set of features themselves.

Organizations must continuously communicate the value of the product and ensure that the gap between the price and willingness to pay is not high.

Scenario 19: W<A<P<V

In this scenario, the customer may perceive the product to offer substantial benefits compared to the price of the product. But he or she may not be willing to pay as it may be beyond their means, and they may perceive it as overpriced.

This scenario is quite common in high price items – such as artworks, limited edition offerings, or more recently NFTs. The price is not aligned with the customers willingness to pay and can lead to lost sales. Organizations will have to re-evaluate their pricing strategy or provide financial incentives to reduce the gap between the price and the willingness to pay. These financial incentives may be in terms of cashbacks or offers or even access to low-cost loans. Organizations will also have to engage in regular marketing and communication efforts to highlight the value of the product. They will also have to make sure that they are targeting the right customer segment.

Scenario 20: W<A<V<P

Products that fall under this scenario will certainly be perceived as overpriced, and beyond the means of the customer.

Organizations that face this scenario need to look at multiple fronts – relook at the customer segment so that the willingness to pay and the ability to pay is increased; increase the perceived value by consistent communication and value-added features; and revisit the pricing strategy to make sure that the customers can afford the product.

Scenario 21: W<P<A<V

Yes, the willingness to pay is low in this scenario, but the perceived value is high, and the product is priced within their ability to pay. This leads to a situation where the customer may purchase the product if there are no comparable alternatives, and if the perceived value far exceeds the difference in price and the willingness to pay.

This scenario usually plays out in the case of high-end fashion items – where the importance of uniqueness, features, craftsmanship etc. very high. The right marketing can help bridge the gap between the customer’s willingness to pay and the value of the product. Showcasing the desirability of the product or offering additional benefits such as exclusive access or customization options, can also help justify the higher price to potential customers.

Scenario 22: W<P<V<A

The major difference between this and the previous scenario is the fact that the ability to pay is higher than the perceived value of the product.

That difference will help the customer to make the decision faster if the strategies that I outlined for the previous scenario is followed. This scenario usually plays out for one-off high-value purchases such as expenses for special occasions like birthdays, or for purchases that are niche or specialty or personalized.

Scenario 23: W<V<P<A

This scenario suggests a situation where customer may find the offering overpriced. The product may not really have perceived value with respect to the price, but they will find it within their financial means.

This scenario normally occurs for high-end, high-cost purchases such as technology devices or exclusive experiences.

The easier option for organizations that find themselves in this situation may be to reduce their price. But they can also focus on communicating their unique features, product advancements, and unique value proposition of the product to justify the higher price. This can increase the perceived value of the product. Organizations can also consider offering buy-back guarantees and loyalty incentives to ensure a greater perceived value.

Scenario 24: W<V<A<P

The willingness to pay and the value is lower than the price. This will lead to a perception of the product being overpriced and of being lower value. The chances of a customer buying such a product are extremely low. This scenario occurs normally for high-price items and customized products, and it is very important that organizations get out of this scenario as soon as possible.

Organizations in this scenario must focus on increasing the customer’s willingness to pay, increase the perceived value of the product, or reduce the price through cost control or by revisiting their pricing strategy.

But Why Can’t Organizations Really Master This?

In such an ideal world, the value must be greater than the price. The willingness to pay must be equal to or greater than the price, and ability to pay must be greater than the price and the willingness to pay. Or in other words, scenario 4 is the best choice for organizations.

But we do not leave in an ideal world. So, even if the prices stay constant, it is virtually impossible to have a constant willingness to pay, ability to pay, and perceived value for any product.

For example, an Uber trip that costs $12 may suddenly ‘surge’ to $100 because of various external factor – a rock concert, snowstorm, or even a hostage crisis. This may lead to the value of the trip, and the willingness to pay to change. An inebriated individual on a New Year’s Eve may value a drop home more than a sober person who may curse Uber for their surge policy. But sometimes things can go for a toss like it did for Uber when its algorithm implemented surge pricing during a hostage crisis in Australia. It was ethically unaccepted and led to widespread public anger. Uber had to release an apology and an explanation of their surge pricing policies.

Barring a few exceptions, no organization can change prices in real time and communicate the true value of their product to the right customer. Even as we live in a world of hyper-personalization and real-time data analysis, the prices and messages of many products are still targeted to broad customer segments than to individual customers.

Organizations may not always be able to set the right price vis-à-vis the value their products and services offer, keeping in mind their customer’s willingness and ability to pay. It also has to do with the complicated pricing process that many organizations still employ, which may not be agile or reactive enough to cater to the evolving needs of the market and the customer.

There is also one more reason why organizations are finding it tough to master the relationship between these four factors. You see, it is very tough to create a completely data-oriented formula that will predict, even with reasonable accuracy, factors such as willingness to pay and perceived value. Even the ability to pay of a customer is an estimation. And the problems with estimations and ‘reasonably accurate’ predictions is that they have every chance of going wrong.

So How Can Organizations Focus on Finding the Right Balance?

Out of the four factors, organizations want three to move in the forward direction – the willingness to pay, the ability to pay, and the perceived value. The customers want to price to move down, whereas the organizations want the prices to move up.

The best approach for organizations would be to break down the problem into smaller parts and focus on each factor.

Willingness to Pay

Organizations need to understand more about the willingness to pay, and the reasons for the customers to choose a particular price point as their walk-away price. They need to conduct market research and perform customer assessments to dig deeper into customer preferences, customer context, price sensitivity, and economic considerations to find out more about willingness to pay for a product.

Ability to Pay

While willingness to pay is an important factor, if the ability to pay for a customer is limited, or low, the chances of the purchase of a product happening is extremely low.

While this factor is a bit beyond the organizations span of control, organizations can focus on being proactive and help their customers increase their ability to pay.

By creating a product that is priced within the ability of the customer to pay and is less than the perceived value of the product, organizations can benefit from a long-term customer relationship.

Perceived Value

It is extremely tough to sell products that have a very low perceived value. Products with a high perceived value will sell out like hot cakes, and with the right pricing strategy, can generate bountiful profits for its shareholders, and optimum delight for all its stakeholders. The focus of any organization must be to continuously increase the perceived value of their products and services.

By focusing on increasing the perceived value, organizations can create long-lasting customer relationships, which may even hold the test of time when the going gets tough.

The Final Word

Organizations need to find the right balance between these four ingredients which may change on a consistent basis. By finding the right balance, they will be able to focus on increasing customer satisfaction, improving sales, and maintaining profitability. But it is easier said than done. The relationship between WTP, ATP, Price, and Value can be complex and influenced by various factors such as customer preferences, market conditions, competition, and individual circumstances.

A strong understanding of the customer, the market conditions, the economic conditions, and the customer psychology will go a long way in helping organizations find the right balance, but the key will be to keep learning, and keep innovating, and being ready for change – anytime, all the time.